Does this world really need another article of mine about The Master? Whatever your answer to this question you’ll have to deal with a new rambling post about the crime writer that matters most to me and, if this blog’s stats are to be trusted, many of you dear readers as well. In the remarkable (impossible?) event that you are not a member of the Carr cult you are allowed to skip what follows. No one is judging or begrudging you for that.

Still here? Okay, let’s go.

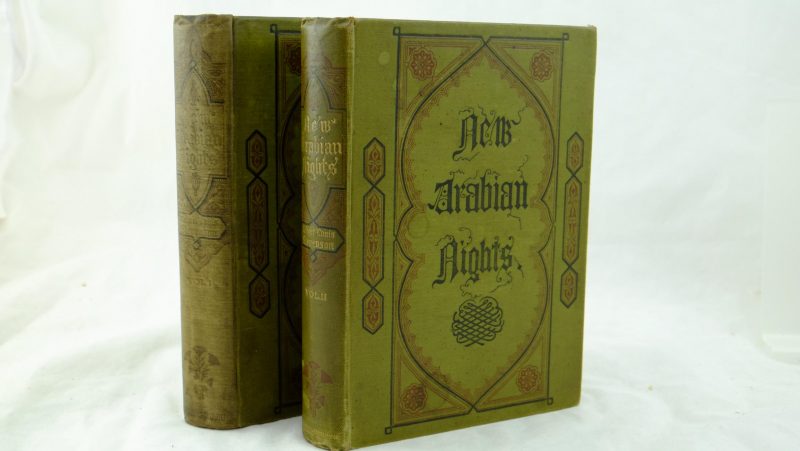

Perhaps I have become tired with the more or less exclusive mystery diet that has been mine for the better half of my life but I have been straying away from crime fiction lately so far that for the first time in a long time my best read of the year so far is not of the criminal sort. It is thus not surprising that I have decided to renew/further acquaintance with some non-mystery writers I had neglected for too long. One of them is Robert Louis Stevenson whom I knew mostly for his novels and his critical essays but had yet to meet on his favourite playground, the short story. I thus dug The New Arabian Nights out of the awful mess that my library is and proceed to read the two cycles involving Prince Florizel. It was late in the evening when I closed the book but I had not lost my time, first because it was great fun and second because it had given me lots of food for thought.

Perhaps I have become tired with the more or less exclusive mystery diet that has been mine for the better half of my life but I have been straying away from crime fiction lately so far that for the first time in a long time my best read of the year so far is not of the criminal sort. It is thus not surprising that I have decided to renew/further acquaintance with some non-mystery writers I had neglected for too long. One of them is Robert Louis Stevenson whom I knew mostly for his novels and his critical essays but had yet to meet on his favourite playground, the short story. I thus dug The New Arabian Nights out of the awful mess that my library is and proceed to read the two cycles involving Prince Florizel. It was late in the evening when I closed the book but I had not lost my time, first because it was great fun and second because it had given me lots of food for thought.

What does it have to do with JDC, you’ll ask. Don’t worry, I’m getting at it (though you should have guessed already if you are a real Carr fan)

Everyone who has read Douglas G. Greene’s amazing, superb, exhaustive and compulsively readable biography of The Master knows that Stevenson was a favourite of young John D. Carr and a strong influence on his early writing, but it took me actually reading RLS to realize how deep and lasting this influence was. The Rajah’s Diamond in particular was kind of a Damascus Road for me. This is not a detective story despite Wikipedia’s classification and there is nothing in it even remotely close to an impossible crime – it just tells of the adventures and misadventures of the titular gem and the people who own or try to own it – and yet it is definitely, eerily carrian in tone and even outlook. The young and naive male protagonists are straight out of Carr’s playbook, and the writing style closely resembles that of early JDC. The atmosphere, though lighter and less gothic, is also the same that Carr imbued in his 30s work. Even the love stories look familiar. If you think the resemblance ends there, you might want to read Stevenson’s critical work too. I don’t know whether Carr did but I guess he would have liked this from A Humble Remonstrance:

« The novel, which is a work of art, exists, not by its resemblances to life, which are forced and material, as a shoe must still consist of leather, but by its immeasurable difference from life, which is designed and significant, and is both the method and the meaning of the work. »

All this is not to say that Carr was a mere Stevenson copycat – there were as many differences as similarities between the two, and most crucially Stevenson loathed the clockwork-like plotting of detective fiction which Carr on the other hand enjoyed and in his prime mastered like very few before and after him. Carr was very much his own man but you’re missing a lot about who he was and what he wrote if you ignore Stevenson’s influence; I might even add if I was in a blasphemous mood that Carr’s decline began when he was finally able to get rid of it.

It is thus puzzling and frustrating that the connection elicited such little interest and comment from Carr fans and scholars . Only Doug Greene and to a lesser and less perceptive degree S.T. Joshi thought it important enough to discuss, probably because they were as interested in Carr-the-writer and not just Carr-the-plotter. The latter tends to get all the praise and attention, which may be why there are no « Carr studies » the way there are « Christie studies » or « Sayers studies ». No one seems to care why and how Carr came to write the kind of fiction he wrote; most/all of the fans’ concern is with how good he was at killing people in locked rooms, a reductive view especially considering that his adherence to the impossible crime formula may have hurt rather than enhanced his writing. In other words Carr is not taken seriously, and this might be one of the reasons why public consciousness keeps eluding him. Praising his admittedly colossal plotting abilities is fine and dandy, but will only work with readers that put the puzzle first and they’re fewer and fewer with each passing year. The resurgence and apparent domination of He Who Whispers over The Hollow Man show that even Carr fans now look for something beyond a masterful puzzle plot. The only way to ensure a Carr comeback in that context is to show people that there is more to him than the locked rooms. Carr may not have been a « great » writer – whatever this means – but he certainly was a good one and it must be stressed again and again.

We have to stop defending and promoting him on purely mystery grounds as this approach has never worked and never will; we must instead make a literary case for reading John Dickson Carr and that requires less adulation and more scholarship. We all want to know how JDC deviced this murder with no footprints in the sand, but what is really important is what led him to write about that in the first place.

I think that you make an important point here. I have always seen Carr as having been hugely influenced by Stevenson. It is noteworthy that Chesterton was likewise a great admirer of Stevenson and it was clear that he was strongly influenced by the great romance writer. As I have argued regularly in the past about the mystery in general, a decent understanding of Carr requires acknowledgement of the nature of crime fiction as romances (even those that claim and strive to be realistic). Stevenson knew this and expressed it superbly in both his fiction and his critical writings, as did Chesterton, who could almost be considered a disciple of Stevenson in the matter of belles lettres.

J’aimeAimé par 1 personne

Stevenson was also a big influence on Jorge Luis Borges who went even further than Carr in the rejection of any realistic pretence. Borges, as we both know, was also a great admirer of Chesterton and avid reader of Golden Age detective fiction. There is clearly a pattern here.

I have written many times both on this blog and on discussion groups about how the mystery genre evolved in the early twentieth century into two separate, competing and mutually hostile schools. One I call The Chesterton School after its most important proponent and has its origins in romance and gothic fiction; the other which I call The R.A. Freeman School aims at greater (if ultimately limited because of the constraints of the genre) realism and accuracy. The Chesterton School ruled over the Golden Age whereas the R.A. Freeman one became dominant after WW2 and has been ever since. Come to think of it, it reminds one very much of the relationship between Stevenson and Conrad, the latter being often described as a more realistic and « mature » version of the former.

J’aimeJ’aime

Stevenson, Conrad, Borges and JDC. The first three are among my five favourite writers. And I’m looking forward to read more JDC next year if only I can find some of his books at a decent price.

J’aimeAimé par 1 personne

Who are the other two?

As pointed out by Lin Wewe over at the FB group Carr’s books – well, most of them – are not that difficult to find or particularly pricey; only first and hardback editions are. I understand that you read French so that may be another option as almost all of his books are available in our language, though in wildly uneven translations. Finally I have many doubles in my collection that I don’t know what to do with, so if you are interested… 😉

J’aimeAimé par 1 personne

That’s very kind of you Xavier, so faar I have about 10 or 12 JDC books unread on my shelf and/or Kindle, but I appreciate very much your offer, mon ami. Merci.

J’aimeAimé par 1 personne

Simenon and Graham Greene.

J’aimeJ’aime

Very good taste – same as mine! 😉

J’aimeAimé par 1 personne

Are there any other Haycox novels that you like?

I think that, like Haggard and Fraser in another direction or aspect of Stevenson, Carr (through superior inspiration and thoroughness of application) solved problems that kept Chesterton and Stevenson (except in Treasure Island) from being the great and effective novelists they wanted to be.

J’aimeAimé par 1 personne

Canyon Passage was my first encounter with Haycox but I can tell you it won’t be my last as I have already ordered all the books of his that I could find – I’m in for a treat if they as good as this one. Any recommendations?

I think you’re slightly unfair to Stevenson as he actually wrote another great novel besides Treasure Island, The Master of Ballantrae, but I can see your point and I agree.

J’aimeJ’aime

I just completed reading the black arrow and I was startled at how through bad judgment stevenson continually screwed up what should have been a very great novel. You’re right about The Master of Ballantrae, though I don’t know how to assess the intriguing (or annoying?) series of anticlimaxes that distinguish the unusual last hundred pages.

My brother has lived the life of an adventurer and loves Haycox. I never read him up to now, but your enthusiasm clinches it.

J’aimeAimé par 1 personne

Call me a stick in the mud (« You’re a stick in the mud »), but I still maintain that as far as « detective fiction » is concerned plot comes first, with characterization being secondary. Not that there shouldn’t be good characterization, mind you, but it’s not primary to this particular subgenre of literature. Mystery writers who put characterization first, more often than not, tend to tug the plot threads apart, so much so that what’s left isn’t much of anything except a muddled mess. And that’s why in my opinion JDC, even with his occasional lapses, is the epitome of detective fiction authors.

J’aimeAimé par 1 personne

I agree with you but we’re sadly not the majority now or in the foreseeable future, so we must find other ways to « sell » Golden Age fiction to the lay reader.

J’aimeJ’aime

Well said Xavier. I will always be a fan of detective fiction and come back to it regularly but must admit less and less so in the last few years. But Carr for me was the greatest of them all – and yes, it’s the impossible crime gambits, the awesome ability to hide the identity of the killer, the humour, the Gothic style and love of shuddery atmosphere. But he was also sensitive and in many ways progressive in some of his views – yes, he was very conservative but not a snob – the conservatism seems to me to have been mostly about politics not social issues. Which is why you don’t get those social and racial prejudices of the day that do occur in Sayers, Christie and even on one occasion the lovely Alligham. And given what a left-winger I am, I would certainly not be able to enjoy his work if I thought otherwise. he was a good prose stylist though some think otherwise – Bruce Murphy in his Encyclopedia has a gigantic blind spot about Carr and really denigrates him as a writer. Really glad to see you say all of this.

J’aimeAimé par 1 personne

One of the many things to like about Carr’s work in my opinion is Carr himself. He was not a perfect human being by any means, but he comes across in his best work as a fundamentally decent person that you would like to meet and have a beer with in real life. Also his love of the genre and his characters shines through his books as well as the fun he had writing them. Like you say his conservatism was not of the doctrinaire sort and is not as off-putting as that of his colleagues may be at times. I’m not even sure he cared that much with politics until comparatively late in his life (the post-war Labour takeover seems to have been his « Great Awakening ») I think he rather was the « Stop the World, I Want to Get Off » kind. The only area where he may be said to have been a staunch conservative is crime fiction or at least in his writing as his critical work shows him surprisingly open-minded at times.

J’aimeJ’aime

I don’t agree with the statement that “The resurgence and apparent domination of He Who Whispers over The Hollow Man show that even Carr fans now look for something beyond a masterful puzzle plot.“ They may, but that statement presupposes the notion that despite He Who Whispers strengths in other areas, The Hollow Man eclipses it in terms of puzzle plotting. I don’t believe this is so. I’ll admit that the puzzle plot of The Hollow Man is more COMPLEX than He Who Whispers, but I believe that the latter work is actually stronger (I’d less complex) superior in that area as well. So that even if readers only valued a masterful puzzle plot, they’d STILL prefer He Who Whispers

Similarly, the usual “defense” of Christie’s Five Little Pigs is that it is superior to most of her other works in terms of characterization. It is, but that doesn’t keep it from being at the very top rung of her puzzle plots, either.

J’aimeAimé par 1 personne